Journal •

The Dublin Architecture Guide 1937-2021

The Dublin Architecture Guide 1937–2021 is a companion guide to the modern architecture of Dublin. The book’s authors, Paul Kelly, Cormac Murray and Brendan Spierin, are leading a cycling tour for Open House Dublin 2022.

With a total of 255 projects featured, this book will suit anyone interested in often under-appreciated or overlooked modern buildings. The guide also includes a foreword by Dermot Bannon and an introductory essay by Jonathan Sergison. From Trinity College to the Docklands, Ballymun to Ballyfermot, Swords to Dún Laoghaire, The Dublin Architecture Guide 1937–2021 celebrates all the brick, timber, concrete, stone, and glass that have helped define the new Dublin of the modern era.

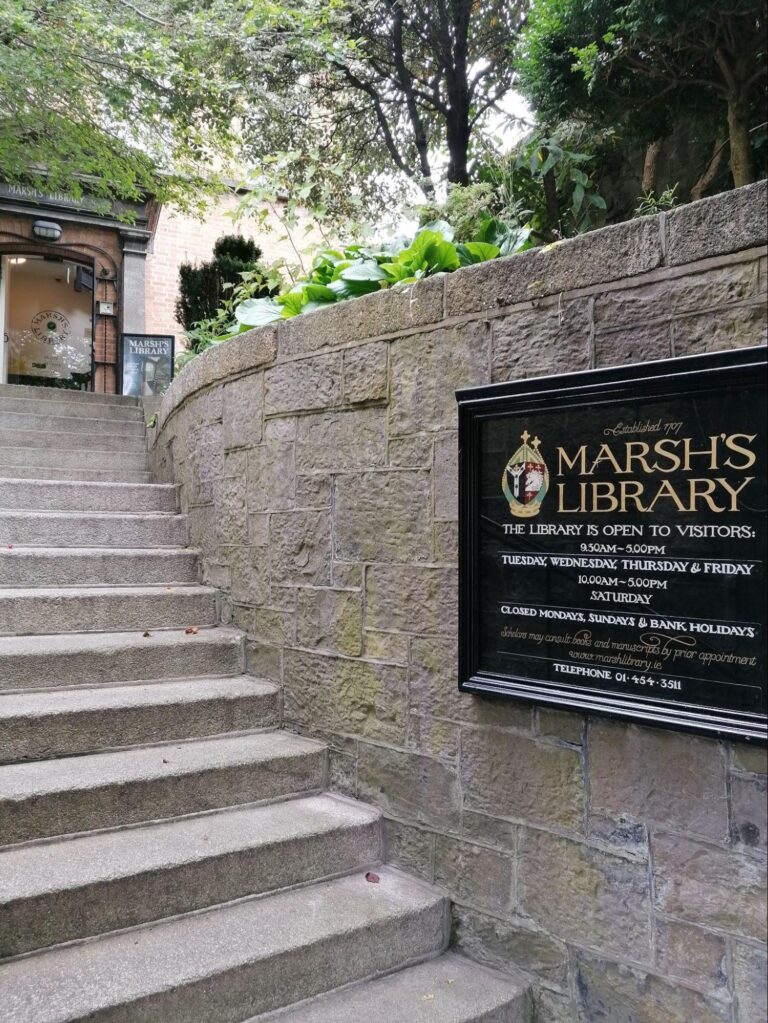

Some of the buildings featured in The Dublin Architecture Guide that are part of the Open House Dublin 2022 programme include: The Exo Building, Capital Dock, The Abbey Theatre, The Museum of Literature Ireland, Busáras, The Berkeley Library, Agriculture House, The US Embassy, and more.

Extract from the Preface:

This book has many visual contrasts: Lansdowne Road Stadium is presented alongside Herbert Mews, a two-storey brick residential scheme; the restored Irish Museum of Modern Art beside a vocational school in Inchicore; the Exo office building beside the single-storey Bord Gáis Above Ground Installation. Contrasts sometimes manifest themselves across one building, such as Sam Stephenson’s Civic Offices contrasting with Scott Tallon Walker’s later addition. Looking at these different buildings collectively rather than in isolation enriches them, seeing marked differences or subtle continuities between styles and eras. As Erika Hanna eloquently describes in Modern Dublin: Urban Change and the Irish Past, 1957–1973:

The city became a site where a multiplicity of identities and agendas were visualized, debated, and given a concrete reality … modern Dublin took its form at the intersection of these tensions.

Previous studies on Dublin’s architecture have been prepared with a sense of urgency and purpose. Niall McCullough, for example, described his ambition to create a better awareness and understanding of Dublin’s undervalued Georgian Architecture in Dublin, An Urban History: The Plan of the City:

The book described the architecture and urban design of the city – and especially the Georgian structure which still formed its core – not as a pleasurable investigation of the past for its own sake but because I thought that the urban structure had great depth and complexity, that it was under-appreciated, and that beginning to unpick it could release ways that I, and other architects, might think about making new buildings in it.

Elsewhere Frank McDonald described in vivid detail the wanton demolition of the city’s historic fabric for profit-driven development. He urged, in The Destruction of Dublin, for councillors and the public to take responsibility for protecting and preserving the city:

People get the cities they deserve. And if our capital city has been reduced to a shambles, it is because we never cared enough to save it.

This architecture guide unintentionally became a means of recording a number of modern buildings prior to their demolition. When McCullough and McDonald were writing in the twentieth century it was the Georgian fabric under threat. Today, many examples of mid-century Irish modernism are under-appreciated and have been erased for more profitable and efficient alternatives. Of the 255 buidlings in this book, only 13 are currently protected structures.

Examples of buildings that have been demolished include the AIB Headquarters in Ballsbridge, the Bord Fáilte Head Office, Fitzwilton House and the ESB Head Office. These buildings are presented as black and white photographs in the book. Sam Stephenson, one of the architects of the ESB Head Office and the enfant terrible of 1960s and 70s Irish architecture, stated in an interview in 1986:

A city is like a woodland which is constantly being changed, replanted, buildings are getting old and being replaced. But you keep a stock of buildings, you keep the best of the past and you add to them with the best of the future. There’s always a pendulum swinging one way or the other.

While we acknowledge that cities have to evolve and regulate over time, we aspire in this publication to promote an awareness of the design consideration behind much of our 20th-century architecture and present these buildings as threads woven into the larger tapestry of Dublin

The Dublin Architecture Guide 1937–2021 by Paul Kelly, Cormac Murray and Brendan Spierin is available now from all good bookshops and from Lilliput Press.

Contributed by Paul Kelly, Cormac Murray, Brendan Spierin